New exhibit at the Nanaimo Art Gallery reexamines life at Nanaimo’s Chinatowns

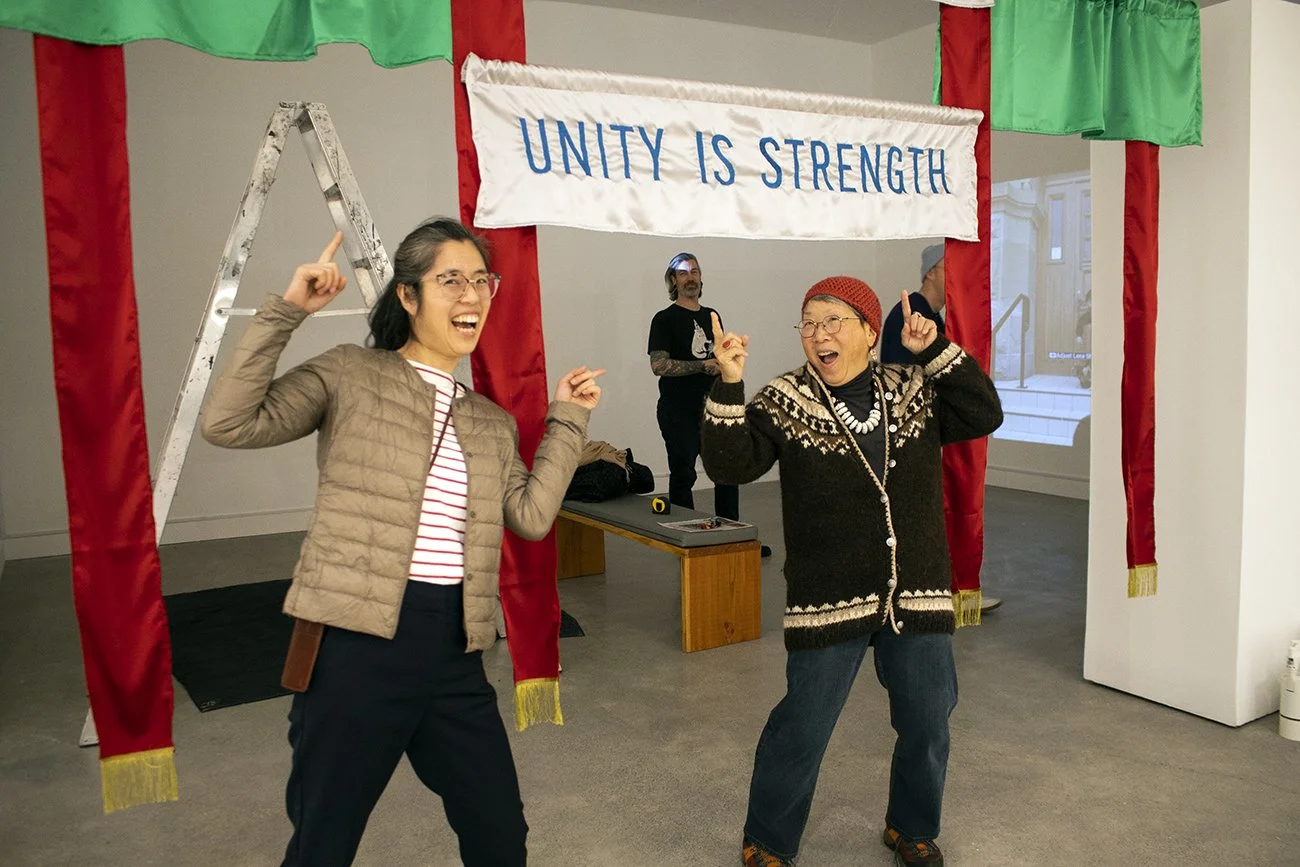

Lim (right) said this exhibit intertwines the past with the current day, with each piece carefully picked to tell a story. (Lauryn Mackenzie/CHLY 101.7fm)

It has been over six decades since the last remaining Chinatown in Nanaimo was destroyed by a fire. Now, a new exhibit reflects on what was and what is now.

Bleached by the Sun: Perspectives on Chinatown,《陽光下的褪色:關於華埠的觀點》is the newest exhibit at the Nanaimo Art Gallery, examining the legacies of Nanaimo’s former Chinatowns through artworks and photographs.

The exhibit shares the history of Nanaimo’s four former Chinatowns. The first Chinatown was built in the 1860s prior to Nanaimo’s incorporation as a municipality, following a coal mining boom in the area.

Three other subsequent Chinatowns were built throughout the downtown area, until the last remaining one was obliterated in a fire on September 30th of 1960.

Photographs by the late Kin Jung and Fred Herzog, as well as paintings by the late Betty Wong, share images of the Chinatowns that once stood and the lives lived in that community.

The exhibit also features three contemporary artists, Charlotte Zhang, Jackie Wong, and Karen Tam. These artists incorporate modern-day perspectives of the community and remember the past.

The exhibit is curated by Jesse Birch and Imogene Lim, 林慕珍. Lim is a retired Vancouver Island University professor who taught in the department of anthropology and the global studies department.

Lim and Tam came down to the CHLY studio to talk about the exhibit.

Tam has three textile works in the exhibit, looking at the historical aspects of Chinatowns.

Karen Tam’s Ruinscape. (Lauryn Mackenzie / CHLY 101.7fm)

“I'm from Montreal, so thinking about Montreal Chinatowns, and just Chinatowns overall across the country, and how they've changed,” Tam said. “Some have disappeared, right? Others have moved to other locations in the city they're in.”

One of her pieces was made during a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I had silk-screened onto satin drawings that I had made during the pandemic of the anti-Asian attacks. Whether it was in Vancouver, or Montreal, or Brooklyn, or Melbourne,” she said. “Then, having them next to other drawings I made based on historic photos of the San Francisco earthquake that destroyed Chinatown, or the fire in Nanaimo that destroyed one of the Chinatowns.”

Lim said this exhibit intertwines the past with the current day, with each piece carefully picked to tell a story.

Lim highlighted the German-born photographer, Fred Herzog, who was made popular for his photos of Vancouver’s Chinatown throughout the 1950’s and 60’s.

“There are four images for Hertzog [in the exhibit], and there's this emptiness, and there's this solitary figure in each of those streetscapes,” Lim said. “Then you have two doorways, and I think the doorways are interesting because I'm also thinking, when I just saw Karen's Ruinscape installed, it's curtains. It's an opening, and then you have these doorways, and it's an opening. So what is it opening to? Is it opening to the future, opening to the past?”

Lim said following the 1960 fire, the memory of Chinatown has faded, with many Nanaimo residents even forgetting that the city once held four.

“We're in the year 2026, so if you think a generation is 20 years, three generations have passed, right? So what does it mean to the memory of a particular place? Because I know people who have moved here, they don't even know that there had been a Chinatown,” she said. “The other thing about not knowing that there had been a Chinatown, again, this is about context. So, before the [Canadian Pacific Railway] had Vancouver as a terminus, Victoria had the largest population, then New Westminster, then Nanaimo. Nanaimo actually had the third-largest Chinatown pre 1885.”

Lim said if you look at any Chinatown, whether it was in Nanaimo, Montreal, or Vancouver, most of the Chinatowns were built in the periphery of the community, pushed to the side.

“So, of course, as the city grows, they encompass it. Then it's like, ‘Oh, Chinatown is kind of in the way. Well, let's have a little urban development.’ Then, poof gets pushed out,” she said. “If you're not a history buff, or if there's no placard, nobody talks about it, you won't know that this had been an actual community.”

Lim brought up how many people may not even realize that historic Chinatowns were based on anti-Asian legislation. (Lauryn Mackenzie / CHLY 101.7fm)

Lim brought up how many people may not even realize that historic Chinatowns were based on anti-Asian legislation.

Chinese and Chinese-Canadian people were heavily segregated in British Columbia socially, academically, economically and politically throughout the 1800s and the early 1900s.

In 1923, the federal government enacted the Chinese Immigration Act, commonly called the Chinese Exclusion Act. The act was passed on July 1st of that year, resulting in a halt in Chinese immigration into Canada. Chinese-Canadian residents were torn away from families back in China, and the growth of the community slowed due to the lack of Chinese-Canadian women in the country.

The act was in place for 24 years before it was repealed in 1947, when Chinese immigrants were finally allowed to apply for citizenship in Canada. Chinese-Canadians weren’t allowed to vote until 1949.

“I think talking about Chinatown, there could be a conflict of opinions as to the good and bad about Chinatown. So the one thing about Chinatowns, I would also say, besides the fact that you had clusters of people of Chinese ancestry, they had so many restaurants. They were open to business for everyone,” Lim said. “I know that in Vancouver's Chinatown, you could go into a restaurant and indigenous people, no problem, black people, no problem. But think about other parts of the city, would they be welcome? No. So Chinatowns were welcoming of everyone, and part of it is because they knew what it meant to be discriminated against.”

Tam said Chinatowns are the heart of a community.

“Chinatown is one of those places where you can gather. Montreal’s Chinatown, for example, is quite small; it diminished in size due to urban development, but for seniors living in Chinatown, it's really important for them,” Tam said. “They can be served in their own language, culturally specific foods, the Chinese newspaper, so they can get all the news, the doctor, the pharmacy, the banks, and everything is walkable as well. So that's really important.”

Tam thought one of the challenges for all Chinatowns is how to keep growing.

Tam (left) said Chinatowns are the heart of a community. (Lauryn Mackenzie / CHLY 101.7fm)

“I guess one thing is for, I guess you could say, ‘visitors’ to Chinatown to realize that Chinatowns aren't just bubble tea and food, that there's like this whole community,” she said. “There are clubs and organizations in the community centers in the basements of buildings. There's a lot of activity happening.”

Lim said this exhibit, just like art itself, is a way to encourage people to expand their horizons and understanding of a community, a place, a memory, and all that it means.

“For some people, the thought of history is like ‘boring,’ and here's a way to approach history in another way,” Lim said. “It may tweak the individual who sees it's like, ‘actually, I don't know a lot about whatever,’ especially because you've taken images of different Chinatowns and different contemporary events, they might want to look up that history and try to understand better.”

Bleached by the Sun: Perspectives on Chinatown will run at the Nanaimo Art Gallery in downtown Nanaimo until March 22. A special opening reception will take place this evening from 7 p.m. to 9 p.m., and a special community event will take place tomorrow, January 23rd, from 1:00 p.m. to 2:30 p.m. at the art gallery.

Funding Note: This story was produced with funding support from the Local Journalism Initiative, administered by the Community Radio Fund of Canada.